- Premise

- Consistency

- How to get participants

- Advertising

- Choosing a topic

- Find your target audience and purpose

- Some things in the competition can be optional

- Get the community involved

- Level of challenge and vision

- Barrier of entry

At the most recent IEEE Conference on Games 2022, Raluca D. Gaina ran a discussion as part of the competitions results presentation session. Christoph Salge and Claus Aranha joined in to express opinions on what makes good competitions, and how to organize better ones in the future. This post summarises the points made, which can be found in the full recording of the competitions session at IEEE CoG 2022 at about minute 1:08:00.

Premise

The discussion started from the premise that we’re seeing more and more competitions being created, some more successful than others. This year there have been 18 competitions running at IEEE CoG, a record number. But some have not managed to attract many (or any, in 3 cases) entries. This can be due to many factors: the still ongoing global pandemic, lack of advertising, lack of general interest, lack of challenge, or maybe too difficult a challenge. So, how can we run better competitions, and what makes a good competition?

Several questions were proposed to support the discussion:

- How to select challenges that will attract interest?

- How to advertise competitions efficiently?

- How to build communities?

- How long should a competition try before giving up?

- How to organize competitions during global pandemics?

- What are key features for competitions in 2023 and beyond?

Consistency

It takes a lot of time and continuity to get a successful competition - most often it does not happen immediately, so the first few editions the competition runs it may not see many submissions. It is key to persist and push it forward. For example, it took the Generative Design in Minecraft Competition (GDMC) 3 years before it started becoming popular and presentable to larger conferences, being now in its 5th year.

How to get participants

University courses are a great source of entries: if the competition is used as course materials, students can dabble in AI, prepare entries for the competition and submit it - meaning a whole cohort of students has extra motivation to participate, as well as being actively told about the competition and encouraged to participate.

Present the competition at conferences - it not only allows potential participants to hear about it and get their interest, but also may give oppportunities for teachers to use the competition in their university courses and therefore create a stream of participants for the next year.

Advertising

First, make it clear that you’re running the competition long in advance, e.g. one year in advance. Has an edition just ended? Announce the next one! Do not wait for acceptance at a conference to tell people about it, this leaves a very short time (usually 2-3 months) for someone to put an entry together, but nobody will plan to put it in a course at that point.

Running a workshop about the competition is a good idea: teach people how to do the competition first. The AI Wolf competition has an organizer do this every year, with 10-20 participants, who then submit entries to the competition. It may take a lot of time to organize and find attendees, however, so make sure you have the resources to do it first. If possible, this greatly helps people get started with the competition.

Advertising takes a lot of work: social media presence is key, perhaps approaching established names with larger audiences to promote your competition. It can take a lot of effort to set up, and a lot of work to constantly push and advertise the competition. If you’re just thinking to set up a competition, make a website, submit it to CoG and hope people will find it, it’s probably not going to get a lot of attention. You need to push and get through that attention economy.

Nice imagery helps and is an advantage, but it’s something a lot of competitions can consider even if they are not focused on aesthetics - we are working with games, so it’s possible to share gameplay videos, or videos of interesting stuff happening.

If you want to get the general public interested, be willing to not necessarily dumb it down, but to reduce it to the funny talking points or stuff that is cool. Do not immediately hit people with the complicated maths, get them interested first.

Choosing a topic

The field is now very competitive. There have been 18 competitions at IEEE CoG this year, and there are big companies or conferences running their own challenges as well. More so, you can win large prizes in the big competitions, that may also be ran at highly prestigious conferences (e.g. NeurIPS). This makes it hard to go up against them with lower budgets and prestige. Given the sheer amount of competitions as well, participants are going to be stretched thin, so you need your competition to stand out and attract their interest.

One way to do that is to focus on the topic chosen: perhaps a nieche which is not the popular topic approached by others, but something that is still very intersting. This way, you can address a different part of the participants pool than what the big companies are going for.

Find your target audience and purpose

It’s hard to choose and find your target audience. YouTube may be a way to get the younger audience. But what is important is who do you actually want to get into this: is it a competition to push back the boundaries of science? Is it for school children to get practice in AI but perhaps nothing world-revalatory? Be clear about what the competition is for and aim appropriately.

Competitions in games also attract people who are not necessarily interested in the science part, but the games themselves. Participants may be motivated by different things: making bots for a game they like to see how far they can get, trying out weird things, doing research, or just having fun. What do you want your participants to get out of this?

Work on the angles from which you pitch your competition, to attract as many people as possible.

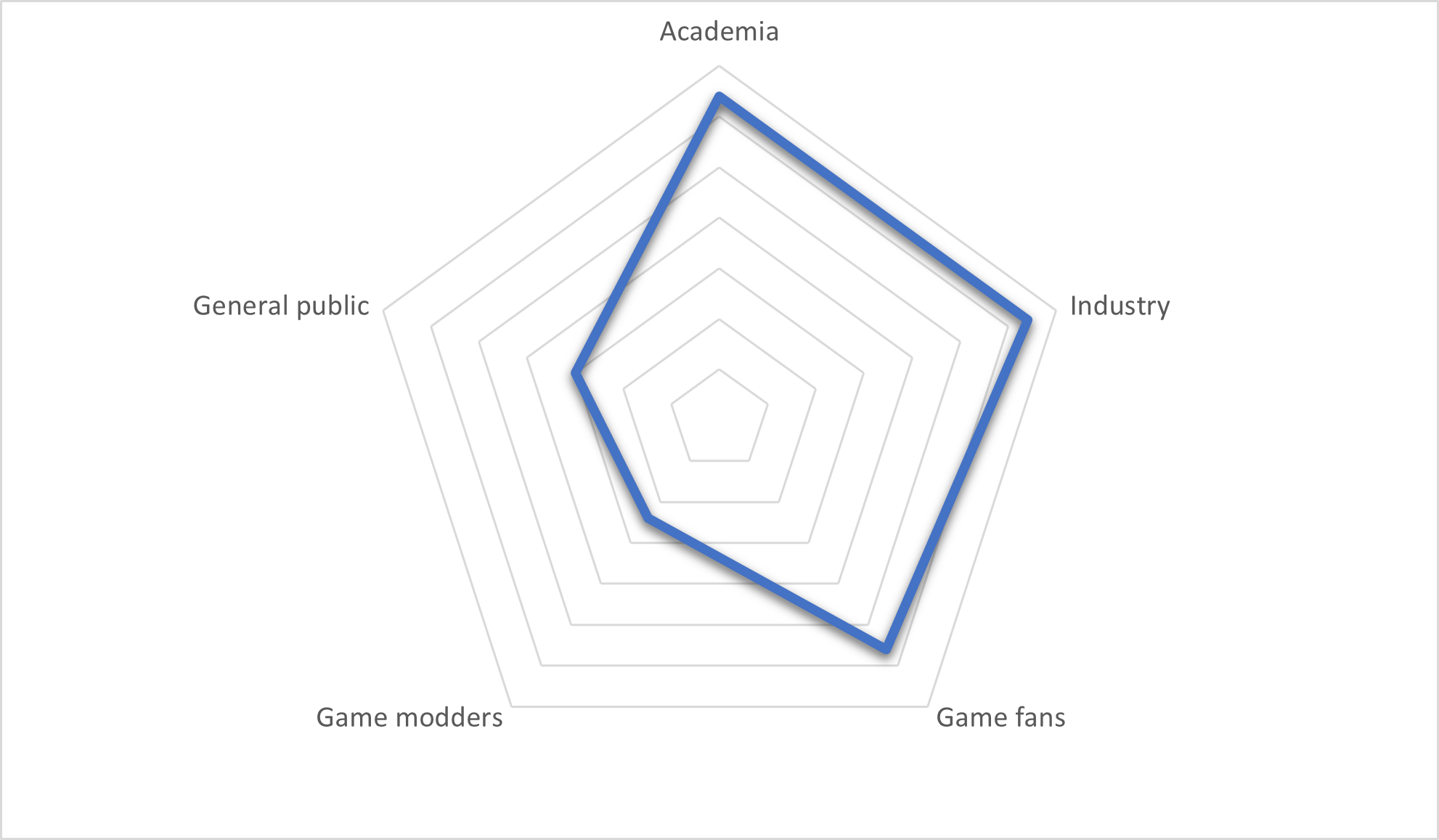

Claus: Connecting back to finding target audience, and to Q&A – competitions should help participants narrow the gap between academia and games industry. Many ways to think about that, what exactly is this connection not only between academia and industry, but also academia and gameplaying community, and academia as the research community vs the study community – several communities that should be linked.

Key questions: What is the audience for the competition? Who are you trying to reach? Bring in people from the communities you are trying to reach. Fun competition? - get people who have fun with the game. Industry competition? - then have people from industry to say what they want. Academic competition? - then have people from academia who are publishing. Each competition will likely lean towards one community or another, or be made up of an interesting combination. Have a vision of what you want your competition to be, plot it out on a graph if necessary, and go after that.

Some things in the competition can be optional

For example, you can encourage code sharing, but some people may think you will be stealing their code, so consider making that optional. If you ask people for a write-up of their submissions afterwards, keep it open as to what this should contain: they may get scared if additionally to coding up their entry, they also have to write “a 4-page latex-formatted document”.

Get the community involved

Talk to your community, set up a discord server, be active on twitter, try to reach out and actively solicit advice on where participants think the competition should be going. Crowdsourcing opinions means a lot more points of view get involved and can reveal issues you’d not think of, or find different areas to focus on that are interesting to them.

It really helps to see it more as a partnership with the participants, rather than saying “we’re organising this, and you’re these passive consumers that are to stay out of the way”. Instead, we should be coming together to push the boundaries of science and do cool stuff.

Level of challenge and vision

It’s great if competition are not too easily solvable. There are so many competitions out there that were solved in 1 or 2 years, because they’re designed by somebody wondering if a certain approach can solve it - and it turns out the answer is yes, it can, and you get 100% completion rate immediately. We’ve moved away from this in recent years and recent competitions.

Your competition needs to have a skill level: if after you clear the barrier of ‘I can run the competition’ you’re close to 80% done, then there’s not much to do and it is not an interesting problem.

If you’re going to make a competition, have a timeplan of where this is going, how to ramp up the challenge, what the final goal is, and also make it a bit more speculative. Not “Here’s the next great application we want to promote for our secret product that we’re already secretly developing”.

Key question: Do you want your AI competition actually to facilitate the comparison between very radically different approaches, do you want something that can be both done with Machine Learning/Genetic Algorithms, but also rule-based simple systems? Or do you want a much more narrow design for a very specific technique that you are interested in?

If a general approach is taken to level the playing field for a lot of different approaches, this can lead to some quirky results and often the more complex scientific approaches failing. It’s something to figure out as an organizer – which direction do you want to go in?

When a competition develops a meta is when a competition gets really fun. Someone will come in to challenge this, and bring in something really weird, different from what people expect – as a participant then, are you trying to make something weird and different and fun, or are you trying to win the competition? The two objectives may become conflicting.

Barrier of entry

Imagine a competition has a server that people’s programs have to talk to, and they have to study the API for the server, and program that – it’s a very high barrier of entry, and it will put many people off. So, anything you can do to lower the barrier of entry is good. For example:

- A framework with standard code

- Some simple strategies

- Sample codes from past years, that new entries can build upon.

Ask yourself: what can you do to make it easier for participants to enter? Consider sharing sample programs that give a very trivial agent that doesn’t have a chance to win, but does something interesting. Both GDMC and AI Wolf competitions have it in common that after you complete the tutorial, your agent can’t win the competition, but it can do something interesting. And that motivates participants.

- Raluca: we’ve encouraged and asked for this at CoG this year to highlight each competition’s barrier of entry level, show some examples -

As the competition grows its community, participants will start making their own tutorials and engaging in different ways: share their resources and encourage the practice, to bring more and more people in.